Where is life better for women – in Poland or in Czechia? It is a difficult question. That is because Czech women can terminate pregnancies, but it costs about 200 euro, so not everyone can afford it. On the other hand, in Poland – unlike in the Czech Republic – we have excellent legal provisions around perinatal care, though the reality in hospitals does not always meet the standards. The Czech Republic has a Breastfeeding Committee at the Ministry of Health, while Polish women have been unsuccessfully fighting for a similar one for years. Poland, on the other hand, has ratified the Istanbul Convention on preventing and combating violence against women, while the Czech Senate rejected the draft resolution earlier this year. One could go on at length about the differences, but isn’t it better to focus on the similarities?

A group of Polish activists from the following organisations: Czułość Foundation, Matecznik, Feminoteka, Rodzić po Ludzku, Mlekiem Mamy and Mały Ssak Association, as well as one midwife, two neonatologists and a civil servant from the Office of the Patient Ombudsman, came to the Czech Republic for a study visit to look at the situation of Czech women and see how we can support each other. They made a similar visit to Norway in April.

Polish women help Polish women in Czechia

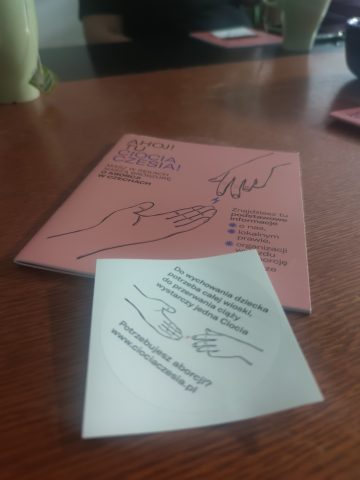

The pink leaflet bears the inscription: “It takes a whole village to raise a child, to terminate pregnancy one Auntie will suffice”. Fortunately, there are three Aunties. Basia in Berlin has been active for 10 years. Wienia in Vienna since September 2020. Ciocia Czesia (Auntie Czesia) is the youngest – it began working just after the tribunal ruling that banned abortion in Poland even in cases of foetal damage or defects.

Marta and Rafał from the Ciocia Czesia collective hand the pink flyers to the study visit participants. They encourage them to take the leaflets to Poland and leave them in a clinic, pharmacy or cafe. Maybe some women in need will find them? Afterwards, they recount the beginnings of their activities.

On October 23, 2020, thirteen Polish women living in the Czech Republic met online. They felt they had to do something to support women who might need abortions. They reached out to other Aunties to learn how to proceed quickly and effectively. One person took care of developing the structure, another of promotion, another of networking. In a wave of enthusiasm, quite a few people offered to help, with translations or financially. Even one pilot wrote that he could transport women to hospitals by helicopter.

The first problem that the Auntie encountered regarded cooperation with hospitals. The law is unclear. Abortion was made legal in the Czech Republic in the 1950s, like in all Eastern bloc countries. At that time a special committee took decisions about pregnancy termination. That was changed in 1986. It was stipulated that abortion up to 12 weeks is legal without a reason, up to 24 weeks if there are foetal defects, and throughout the pregnancy if the woman’s life is at risk. However, it was also stipulated that only Czechoslovakian citizens could access abortion within the country, unless another law took precedence. And even though Czechoslovakia no longer exists, the provision is still valid, and hospitals interpret it in various ways. Especially since the Chamber of Physicians says that Polish women cannot have abortions in the Czech Republic. While the Ministry of Health maintains that EU law is paramount, and abortion – like any other medical procedure – should be available to all EU citizens.

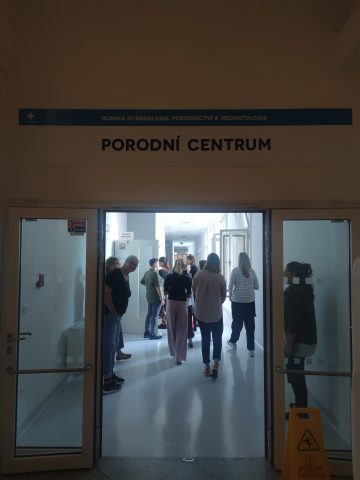

Nevertheless, in the end Ciocia Czesia was able to establish cooperation with two clinics in Ostrava, one in Brno and one in Prague, as well as two hospitals in Frýdek-Místek (abortions after the 12th week of pregnancy can only take place in state hospitals). They agreed to receive Polish women.

How does it work? A woman in need can write an email to Ciocia Czesia. The person on duty will help. If necessary, they will give emotional support (this is often the first time a woman talks to someone about abortion). If asked a question about the possibility of terminating the pregnancy, they will usually advise a medical abortion at home, in Poland. It is best to order pills from Women Help Women or Women on Web. These organizations do not ship pills to the Czech Republic, where they are only available in hospitals and only up to the eighth week of pregnancy. Most abortions in the Czech Republic are surgical procedures. So, if a woman who is determined to have an abortion in a hospital writes asking for the name of a clinic, Ciocia will help make contact. If foetal abnormalities are found, they will make sure to send an ultrasound with a description and other tests. They will inform the woman that she must also visit the local geneticist to receive an official indication for the procedure.

Most importantly – abortion is a paid procedure. For Polish women, it costs about 2,000 zlotys for an abortion up to the 12th week. Later procedures can go as high as 5,000 zlotys. Czech women also pay, just a little less. Thus, if a woman needs financial support, Ciocia will also help. They can either contribute to the procedure or pay in full. This year, seventeen people have asked them for such support – for a total of almost 6,500 euros. People generously support Ciocia, so it hasn’t happened yet that they’ve had to say no to someone.

They helped a mother with two children, including one disabled. She runs her own business and couldn’t imagine taking care of a newborn (though in the hospital no one asked her for a reason for her decision). They helped a woman whose pregnancy was the result of spousal abuse (she is not sorry she had an abortion; she is proud that she finally stood up for herself). They helped a woman for whom three-step contraception had failed – the pill, a condom, and finally even emergency contraception (after the procedure all she felt was relief).

When Joanna Gzyra-Iskandar, an anti-violence against women advocate at Feminoteka and a member of the Legal Abortion collective, listens to Ciocia Czesia’s story, she senses red flags a few times. Especially when discussing the situation of Czech women.

She is struck by the economic aspect – they must pay about 200 euros for access to abortion, even in a state hospital. Yet abortion is a basic and inexpensive benefit. Such fees force some women to either carry a pregnancy to term or borrow money. Or perhaps even to seek alternative, not always safe, methods of terminating a pregnancy. International organizations don’t send pills to the Czech Republic, women can’t get abortions at home, and this can create the danger of the emergence of an abortion underground. Besides, why don’t doctors follow the WHO guidelines that state that medical abortion is safe and carry it out only until the 8th week?

Joanna experienced an activist awakening during the black protests in 2016. It was then that she realized that half of society was facing total injustice and decided to fight against it. In the Legal Abortion collective, she is involved in spreading proven abortion knowledge, raising public awareness, social campaigns and advocacy. Occasionally, she receives questions from women about what options they have when needing to terminate their pregnancies. And there are two options – the pill or going abroad. If a woman chooses the latter, Joanna directs her to the Abortion Without Borders network, to which all three Aunties belong.

“I’m grateful to them for their help, but I’m also far from idealizing other countries when it comes to abortion access,” Joanna concludes. “Czech law is better than Polish law, but it also creates barriers for women.”

Czech and Polish women fight with the patriarchal system

We also learn about perinatal care. Representatives of Czech midwives’ organizations are waiting for us at the headquarters of Aperio, an organization that supports parents. Particularly looking forward to these meetings is Paulina Nowińska, a Polish midwife and lactation consultant. She runs her own practice and works under contract with a hospital. She came to the Czech Republic at the invitation of the Czułość Foundation, with which she will start cooperating soon. When Czech midwives talk about their situation, all the difficult moments she experienced at work play out in her head.

For example, when Lenka Laubrova from Apodac, an organization that fights for Czech women to be able to give birth outside hospitals, tells how midwives are obstructed from assisting home births. Until recently, they could even be heavily fined for doing so. Yet one can find those who have the courage to be outside the system. They take risks and deliver babies, and then tell doctors that everything happened so fast, there was no time to travel to the hospital. Or that when they showed up at the address, the baby had already been born.

Paulina then thinks that maybe things are better in Poland. We have an excellent law – women can choose whether they want to give birth in or out of hospital. However, home births are not financed by the National Health Fund, so women must pay for the presence of a midwife who has her own practice and liability insurance. So, the law is good, but also in Poland few midwives choose to assist home births. Perhaps because the equipment needed for this is very expensive. But perhaps even more so because they often don’t have anyone to learn from. In college, professors told Paulina repeatedly that home births are dangerous, and now opinions are divided. So, in our country, too, a midwife who wants to accommodate a woman’s needs must break the patterns, and sometimes she is treated as an enemy by the system. It takes a lot of inner strength to go for it.

Paulina is also perturbed when Marie Vnouckowa of the UNIPA midwives’ union tells how in the Czech Republic, midwives work in hospitals under the strict supervision of doctors and are not allowed to prescribe medication or order tests themselves. After three days, the parturient goes home and receives no further care. A midwife can visit her only on the explicit recommendation of a doctor. UNIPA therefore demands that midwives become full-fledged providers of perinatal care, so that they are in a strong position.

In Poland, the legal situation is somewhat better in this regard as well – midwives can prescribe selected medications and order tests. A woman is not alone after giving birth, a midwife visits her up to six times. Paulina knows what it is like, because before she started working in childbirth, she was a community midwife.

“That’s exactly when I started to think that perinatal care is not only a medical event” she recalls. “I understood that I am not coming to check how the woman is taking care of her baby, I do not conduct an exam on weight gain, on bathing, on clothing. I come, because that woman has plenty of questions and she trusts that I know the answer. I accompany her during an event, which for her is a phenomenal experience, often spiritual.”

Maybe it is because of her empathetic approach that she has heard so many childbirth stories from women, some of them terrifying. Because violence is still present in the delivery rooms. It may take the form of words – someone addressing the woman impersonally, with superiority; someone saying: “Lie down, lady!” in an unobjectionable tone. It can also be actions – forcing a woman to stay in a position she doesn’t want; conducting transvaginal examinations when they are not necessary, often without asking.

“I hurt as well when someone does this in my presence,” Paulina admits. “Violence towards a woman giving birth is also violence against me.”

It happens that while she delivers a baby, she feels under pressure, especially when a gynaecologist enters the room. There are those who will help, when necessary. They will apply pelvic pressure, for example, but there are also those who stand behind her shoulder and just huff. In such cases, she feels as if she were taking an exam.

Thus, maybe in legal terms, midwives in Poland are better off than those in the Czech Republic, but Paulina Nowińska sees patriarchy in midwifery all the time. Both doctors and midwives are sometimes violent. At the root of this problem lies education. Paulina was taught that it was up to her to know what a woman in labour needed. She quickly realized that this was not true. After all, she doesn’t know how a woman feels, if she is in pain, what she is afraid of. It takes courage to ask.

The third moment that stirred her came when Daniela Vorlova, from the Aperio organization, said that the way we come into the world matters. Paulina thought that midwives in Poland have similar slogans, such as: “Quality of labour is quality of life.” If the mother is satisfied with the birth, feels taken care of, there is a better chance that she will take good care of the baby. But what if she has just experienced the most difficult moments of her life? If she kept getting information that she was giving birth wrong and cared for the baby badly? She will feel insecure, and this will affect the first months of the baby’s life.

Paulina quickly realized that she wanted to change something in the systemic approach to childbirth because, after all, she is also a woman, a patient, and was treated in various ways. “If you want to change something in the world, start with yourself,” she thought, and began to participate in miscellaneous training courses. She sensed that she had not acquired certain skills in college. She took a training course for lactation consultants and within maternity care. Today she understands that she was lacking in soft skills, she didn’t know how to pay attention to the mental and emotional state of the parturient, how to talk to her when she was experiencing something difficult. Problems with breastfeeding, for example, are often combined for a woman with the question of whether she is a good enough mother. It’s important to be able to pay attention to that. Thus, Paulina changed her approach to work. Today she proudly says that her greatest competence is knowing how to accompany women. “Is there anything I can do for you now?” is the question she asks birthing women most often.

But she also has small systemic successes. At the hospital where she used to work, she always asked mothers who were separated from their babies for health reasons if they planned to breastfeed. If they were planning to, Paulina asked if she could collect milk and bring it to the baby. This required her to walk 48 steps. Younger colleagues began to ask why she was doing this. She answered that if the colostrum is expressed up to two hours after birth, there is less risk of lactation complications. And by the time she left that hospital, a whole team of young midwives was collecting colostrum from mothers. So, she was able to take a step in the right direction. She hopes to do more.

When Paulina listens to Czech midwives, she feels solidarity. Maybe there are better laws in Poland, but culturally we are very close. Both in Poland and the Czech Republic, midwives are forced to struggle against the patriarchal system in hospitals. Those who want births to look different, who listen to the voices of women in labour, face difficulties in both countries. We are not alone.

Czechs training Poles

Anna Furmaniuk from Matecznik Foundation draws a “problem tree” with a red marker on a piece of paper. The tree is part of an advocacy workshop with Jana Smiggels Kavkova, a Czech feminist and activist, and Stepan Drahokoupil of Open Society Prague, and the problem is the issue of underage mothers’ rights. There aren’t many of them in Poland, maybe a thousand women a year, yet each of them is important.

The tree looks as follows:

Problem: Young mothers do not have rights to their children. (Mothers aged 16-18).

Source: Bad law. (An underage woman who gives birth has no rights to the child, her guardians are the ones to take decisions about the baby. Polish law allows the girl to become emancipated only if she marries, not necessarily the father of the child).

Negative consequences: Lack of choice. A disturbed mother-child relationship. The provision afflicts the agency of minor mothers.

Matecznik Foundation would like to change the current law so that girls can also emancipate themselves by court decision. Then those who wish to take care of their child and have the conditions to do so will have this opportunity. It’s seemingly a tiny change, adding a few words to a paragraph in the code, but the next step in the workshop, in which one needs to map out opponents and allies on the way to achieve the goal, is causing Anna and her group more trouble.

“The workshop with Jana made me realize that changing the law is not such a simple matter,” she says. “We don’t quite know yet exactly what the legislative path is, and which people should be interested in the problem.”

The Matecznik Foundation, which supports women in the perinatal period, is taking its first steps in advocacy. The foundation was established in 2016, in part because Anna Furmaniuk got angry. After giving birth to three children, she began teaching women how to carry their babies in slings. This helped them not only in their daily lives, but also in building closeness. She did this for ten years and listened to childbirth stories and watched tears shed. Very many women have had difficult experiences – during childbirth they felt humiliated, unimportant. The staff often wants the woman to submit, they don’t give her information about what’s going on or they comment on her appearance. And when you give birth to a baby, the body is out of control and it’s not the time to mouth someone off. So, Anna got pissed and decided to open a birthing school. Maybe then women will be better prepared for what awaits them? She and Alicja Nowaczyk also organized a workshop on rights in childbirth. It turned out that the law is not boring at all, and its violation awakens women’s fury. They realized that this is an important topic. They registered a foundation.

The mission of the Matecznik Foundation is: “Woman. Mother. Citizen.” Anna and Alicja want Polish women to be strong, aware of their rights and not afraid to fight for those rights. They conduct perinatal education for women and their partners, but recently they have been putting more and more emphasis on psychological support. It started with the foundation providing several women with free support from a psychologist. During the pandemic, more and more women were interested; those expecting a baby were in fear of giving birth around Covid. There was also a response from female psychologists who wanted to volunteer. The foundation began looking for sources of funding. Now several women in need contact them every day, and they try to provide each one with a minimum of three meetings with a psychologist.

Among those in need, two groups stand out. One of them includes women who fear childbirth, they are afraid that they will not be able to bear the pain. This fear interferes with their daily functioning.

“Pregnancy can exacerbate emotional crises,” explains Anna Furmaniuk. “A woman knows that she should buy a crib or stroller, do research and choose a hospital, but the important task for her is also to sort out various issues in her head. She may be worried about relationships with her family, problems at work, in her marriage. It is good for her to deal with these emotions.”

The second group that asks for psychological support is women with bad experience of childbirth. They are traumatized, broken, humiliated. This could be postpartum depression or even PTSD, like the kind that affects soldiers returning from the front.

“It’s a matter of biology,” Anna explains. “Hormones during labour work properly if they are not disturbed and are correctly supported. They transmit information that regulates various processes. Oxytocin is responsible for creating a bond between mother and child. Prolactin supports the mother’s adaptation to her caregiving role. Endorphins help a woman forget about pain. However, when these hormones are interfered with, as it happens when there are too many interventions in the natural course of labour or because the woman is mistreated, the hormones may not work as they should.”

Women then have difficulty establishing a relationship with their newborn. They also feel remorse, because they expected to be flooded by love, and yet they feel empty. This doesn’t mean that the bond won’t appear afterwards, especially if the mother is cared for. It may happen after a few days, weeks or even months. However, this does not change the fact that something was taken away from the woman at the start.

The Matecznik Foundation also provides women with advice on labour law or patient rights. They have had considerable success. Recently, two women who benefited from the foundation’s psychological and legal support decided to file complaints with hospitals. Both fought for financial compensation, and both succeeded in obtaining it. This is gratifying, because wronged women often do nothing. Yet the point is not only for them to get closure, but to try to improve the situation of those who will give birth later.

Now the Matecznik Foundation also plans to start advocacy efforts to change the law. They will soon hold a workshop to learn how to be advocates. Perhaps after it is over, they will attempt to change the law on the emancipation of young mothers. The workshop with Jana helped them take the first step in this direction.

Polish and Czech women replace the state

There is a post office on the first floor of a three-story building in the Brevnov district. A lot of people go in and out of it throughout the day. Therefore, people who head to the second floor get lost in the crowd and no one pays attention to them. And this is where PORT, the country’s first help centre for women with experience of sexual violence, has been located since January 2024. It is run by the proFem organization. Petra Presserova from the legal department gives us a tour of the spacious premises. She shows us three rooms with soft armchairs. The first is for crisis intervention. Any woman in need can come here on weekdays from 9 am to 6 pm and get help. The second – for individual therapy. In the third, hearings are held. There are cameras in it, so lawyers or other interested parties can stay in a separate room so as not to further stress the victim. There is also a doctor’s office, where women can be tested for sexually transmitted diseases and administered emergency contraception. Petra notes that they will try to make sure that evidence can also be collected and secured here, but it is still unclear whether it will be accepted in the courts.

But PORT’s greatest pride is a small room decorated in wood and light green colour. There is a bed, a washing machine, a small kitchen, a cozy bathroom, clothes in the closet and food in the refrigerator; that is, everything you need to live. This is an apartment for a woman and two children. A person in crisis, if she needs to move out of her home urgently, can live here for a week or two and benefit from the centre’s psychological or legal counselling.

ProFem has plans for similar centres to be opened throughout the country. Because the problem of sexual violence against women is still immense in the Czech Republic, with 890 people reporting rape to the police last year. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Estimates suggest that the problem affects 14,000-15,000 women a year. The state doesn’t offer them any systemic help. Petra says that a woman who has been wronged often has to visit as many as fifteen places and recount everywhere what happened to her. It would be ideal if she would be able to get everything done in one place, such as PORT. However, the authorities have no plans to establish such places. PORT is funded only in one-twentieth by public funds, with the rest of the money provided by grants and private sponsors.

Joanna Gzyra-Iskandar knows this problem very well. The “Femka” post-rape help centre, which Feminoteka runs in Warsaw, has no state funding at all. There is also no public support system in Poland for people who have experienced sexual violence. Therefore, both organizations operate under similar conditions. Their offer is also similar. They differ only in details. Femka’s address, unlike PORT’s, is not made public. You can’t just simply come here; you must make an appointment by phone. However, women can get legal, psychological and social support free of charge, benefit from a support group, yoga after trauma, or assistants who will go with them to the hospital or to the police or court to monitor the process.

“We try to make our offer as wide as possible so that each person who approaches us can choose what they need,” Joanna emphasizes.

Women can live in Feminoteka’s shelter for up to several months, for as long as they need it. It is mainly used by refugee women, who have fewer opportunities to obtain social or community housing. Of course, they receive support in the process of becoming independent.

During the first year of activity, about 200 women, mainly from Poland, but also from Ukraine, have benefited from Femka’s assistance. The hotline receives an average of 120-140 calls a month. Some simply want to ask something: Was what happened to me violence? Do I have to report the rape to the police? Sometimes witnesses who see something disturbing happening in their neighbourhood call because they wonder what they should do. Reports of sexual violence account for about a third of the calls, another third are about post-separation violence, when partners or husbands continue to try to use violence after a breakup – for instance, deliberately prolonging lawsuits. Feminoteka will help everyone. Just like PORT does.

“I feel heartened by the fact that the girls from proFem have done so well in raising money, renovating the premises, and planning how the centre should operate,” Joanna Gzyra-Iskandar emphasizes. “In a way, they are in a more difficult situation, because the Czech Republic still has not signed the Istanbul Convention, which imposes an obligation on the state to create centres for people who have experienced sexual violence. Poland has signed it, although it is only moderately complying with its obligations, but we have a strong argument facing the government under international law.”

Joanna was also struck by how similar the problems are that the two organizations have to deal with.

“ProFem wants to educate police and judges about sexual violence, “Joanna recalls. “At times they manage to organize training for the police, and at other times they don’t, it’s hard to talk about regular cooperation. And judges are completely inaccessible. “We see exactly the same thing in Poland.”

Because Polish and Czech women function in a similar reality, they struggle with similar problems. Some solutions are better in the Czech Republic, others in Poland, but we can look at our strategies and learn from each other – like Femka from PORT. We can also help each other get around inhumane laws – like Ciocia Czesia; train in effective advocacy like Jana Smiggels-Kavkova or build a sense of professional solidarity like Polish and Czech midwives who struggle with the patriarchal system in hospitals. Then – both in Poland and the Czech Republic – women will have a better life.

The study visit to the Czech Republic on reproductive rights and perinatal care and support for people who have experienced sexual violence, was held under the Active Citizens – National Fund program with support from the Open Society Foundation in Prague.

Text: Urszula Jabłońska

The report was published on Onet.pl