When Anna saw the two lines on the pregnancy test, she immediately set up a gynaecologist appointment. The doctor did an ultrasound and confirmed the pregnancy – sixth week. She told him that her boyfriend had doubts, not being sure if he wanted to become a dad. The physician asked what she was planning to do in that case. She said she wanted to have the baby. She was referred to a midwife who would be the one to care for her during pregnancy.

She had a private room during labour and was accompanied by her partner throughout the whole time. The birth’s progress was monitored by midwives at a special station. When she said that she needed an epidural, the doctor arrived within five minutes. Long hours passed and the child still wouldn’t arrive. Her amniotic fluid turned green, the atmosphere became tense. The midwife told Anna to push, that there was no other way. So she pushed for two and a half hours, screaming from the top of her lungs. The child’s shoulder was, however, stuck, and a vacuum had to be used.

Kuba was born blue. The doctor ran with him from the delivery room. After a few minutes the child’s father learned that the situation was under control. Anna was in bad shape as she had lost a lot of blood. After two hours she was taken in a wheelchair to see her son and take him in her arms.

Later, the parents were moved to a nearby hotel and waited there for a week until Kuba was able to leave the hospital. They had three meals a day and beverages provided. Next to Anna’s hotel bed there was a button to call a midwife or a nurse at any time of the day and night. Midwives encouraged her to pump milk. There was a special room in the hospital for this.

‘Despite a difficult childbirth I have only had a positive experience with the healthcare system, both during the pregnancy, as well as from delivery and later care,’ says Anna. ‘At first I’d tell myself I’d never want to give birth again, but now I think I would do it and it would be a natural childbirth.

Anna’s experiences were good, because she was provided with the freedom of choice, professional perinatal care and breastfeeding support. Did she give birth in Poland? No. In Norway. A group of Polish and Czech activists from social organizations that work on women rights travelled to Norway for a study visit in order to look at solutions within family planning and perinatal care, which ensure that women are treated with dignity.

First stop – the choice

Marcelina Kurzyk from The Foundation for Women and Family Planning „Federa” looks around the clinic of the social organization “Sex og Samfunn” (Sex and Society). There is a reception desk at the entrance, where you can scan a code in order to sign up for a consultation, further on there is a waiting room adorned with LGBTQ+ flags, doctors’ and nurses’ office , and an examination room. Anyone, who isn’t yet 25 years old, can come here for a free consultation regarding available contraception methods, get tested for STDs and obtain a sexologist’s advice. Marcelina likes the fact that even if someone comes outside of the opening hours and the clinic’s doors are locked, they can take some condoms and lube sachets from a special stand. ‘In Poland people still associate lube with vaginal dryness during menopause, not necessarily with greater pleasure during sex,’ she comments.

Marcelina looks carefully at how the clinic operates, because Federa is planning to open a similar one in Warsaw. It is important for the city to have a place where women will have access to doctors, who will certainly not invoke the conscience clause when prescribing contraception, including emergency contraception. And also access to a psychologist, who will help them deal with difficult experiences, for instances with post-abortion emotions. They may be varied, it is not always relief. Federa plans to set up space for sexual education workshops on the first floor of the clinic.

It might seem that the clinic in Oslo and the one planned in Warsaw would be similar, but there are, however two major differences between them. Firstly – the one in Norway is mostly financed by the city, the Polish one will be a social organization’s initiative. Secondly – they operate under completely different legal conditions.

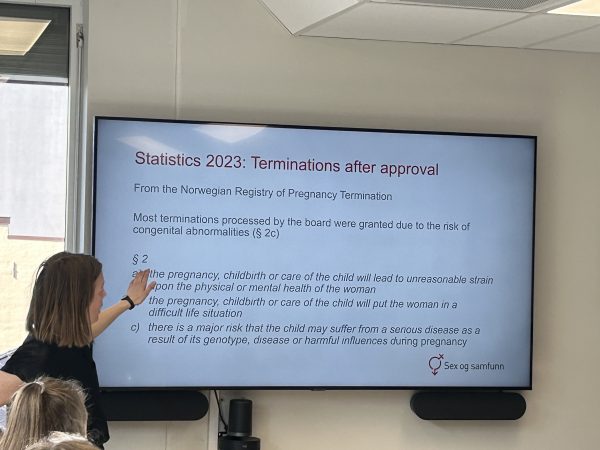

In Norway abortion on demand up to the 12th week of pregnancy is available since 1978. Women may simply call the hospital and say: ‘I’d like to terminate my pregnancy’. Nobody will ask them unnecessary questions. Within one or two days the woman will come to the facility, take mifepriston, progesteron’s antagonist. She will also receive mizoprostol to administer at home. And that’s it. If she would want to have an abortion later than in the 12th week – usually these include cases when women learn about foetal defects during an ultrasound – she has to present a justification in front of a medical board. But in these cases there is usually no problem either. In 2023 the board has given positive opinions to all 610 requests. Despite that, Anneli Ronnes from „Sex og Samfunn” explains that further liberalization of the Norwegian law is necessary – abortion on demand should be possible until the 22nd week of pregnancy. Bureaucratic procedures are unnecessary since women always get consent for the intervention anyway.

By contrast in Poland abortion of demand is not available at all. Pregnancy may be terminated only when it is a result of a crime or when childbirth is a risk to a mother’s health or life. Therefore women who carry unwanted pregnancies call social organizations, including Federa. Women are never punished for their own abortions. Informing about the possibility to terminate pregnancy is not a problem either. The penalty is only for aiding and abetting, i.e. handing over the pills or inciting someone to have an abortion. So when Marcelina picks up the phone, she advises the women to order pills from a foreign aid organization – Women on Web or Women Help Women. You have to pay a donation and wait till the pills arrive by post.

Federa, as the only organization of its kind in Poland, also takes care of organizing abortions in Polish hospitals in cases of identified foetal abnormalities. The women who call have just received the results of prenatal tests. They are heartbroken because they have often struggled for many years to get pregnant, some only succeeding after IVF. They already have a cot and clothes, and suddenly it turns out that the foetus has no brain.

Marcelina first assures them that she will not leave the woman alone. She then provides information about the procedure, which is not at all complicated. Foetal abnormalities are not an indication for abortion, but a woman’s poor mental state is. The results of an ultrasound examination and a chorionic villus biopsy or amniocentesis are therefore necessary. In addition, a psychiatrist’s opinion is needed to confirm that the pregnancy has a negative impact on the woman’s mental health; as well as a referral from a gynaecologist to a pregnancy pathology ward. It is important for the doctor not to write down the name and details of any particular facility, so that the woman can choose a hospital on her own. Usually the one in Oleśnica.

‘It is our refuge,’ explains Marcelina Kurzyk. ‘However, if it is early in the pregnancy and the woman feels up to it, we encourage her to go to the nearest facility. Maybe there won’t be a problem? After all, we are acting within the law. The Patients’ Ombudsman has given a clear opinion that a threat to a woman’s mental health is a reason to terminate a pregnancy.’

At least one woman per day calls Federa. In 2023, the organization helped 3,544 women with unwanted pregnancies, 1,145 with a defective pregnancy, and 13 pregnant as a result of a criminal act.

‘Women are often afraid to enquire about abortion directly,’ says Marcelina. ‘They only say: „Hello, I need help” and we know what it’s about. I really like that in Norway there is no such taboo; that women have nothing to fear. It should be the same in Poland – abortion is a normal thing.’

In recent years Marcelina has seen the fear growing amongst Polish women. She wrote her Bachelor’s thesis on the social determinants of fear against unplanned pregnancy. This was immediately after the Constitutional Court’s verdict in 2020, which tightened the abortion law. Twenty-four out of thirty people she interviewed admitted that since the verdict they fear unplanned pregnancy even more.

As a sex educator, Marcelina replies to e-mails from youth and three quarters of questions revolve around the subject: ‘Could I have gotten pregnant?’. ‘Was it possible to happen through petting or if sperm was on my leg?’ Sometimes girls write that they take contraceptive pills, additionally use condoms and the pull-out method. ‘Is it enough to avoid pregnancy? Can beer diminish the effectiveness of contraceptives? What about vitamin C?’ Young people have it inscribed in their minds that abortion is banned and access to the morning-after pill limited. In case you accidentally get pregnant, you are in a fix. This awareness heightens anxiety.

Regarding contraception, Norway and Poland are completely different. In Norway, the majority of contraception is refunded or completely free for people under 22. Doctors and nurses give thorough information about the possibilities to prevent pregnancy. A school nurse may place an contraceptive implant under a schoolgirl’s skin. At the same time in Poland, according to European Contraception Policy Atlas’s research, we have the worst access to contraception in all of Europe and have had for several years. Federa organizes workshops on sexual education in schools – for students, parents and teachers. The topic of contraception always pops out. Young people have no access to reliable sources of information provided by the government. They get information from Facebook groups or from friends. Therefore activists take care of sexual education, provided they are allowed to enter the school, because it is not always a given. Federa publishes their own brochures about contraception, STDs, emergency contraception and informed consent. They have been tested by specialists.

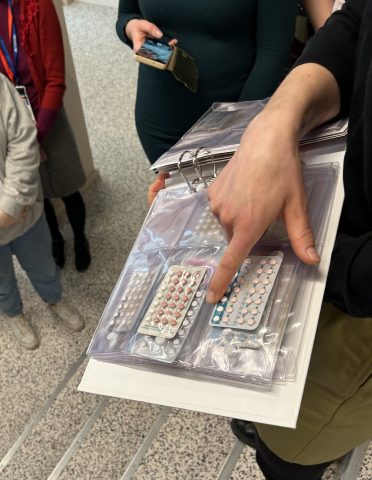

‘What I really liked in the Norwegian clinic was a binder with various types of contraceptives, which you can take out and look at,’ says Marcelina. ‘It often happens that girls aren’t really sure what they are taking. Such a binder would be very helpful in such cases. The problem is that it is hard for us to get a hold of an IUD or pills even for workshops, as we are not a medical entity.

In „Sex og Samfunn” employees use the binder to display various contraception options. In Poland it is difficult to get professional contraception counselling. Often gynaecologists prescribe pills straight away and do not inform about other options, for instance implants, vaginal rings or patches. They often refuse to insert an IUD if the woman has not given birth. Or they refer the patient to a private practice, even though they can insert it free of charge. Privately, it costs around 1,000 to 1,300 PLN. On Federa’s website there is a database of clinics that have a contract with the National Health Service and should insert IUDs for free.

Marcelina loves her job. Maybe it will sound strange, but she has been interested in contraception since she was a kid. She dreamed about working for Federa when she was still a student at uni. She feels content, especially when she picks up a call from a crying woman who doesn’t know what to do and at the end of their talk she hears: ‘Thank you! You’ve helped me so much!’. But she also knows that it is necessary to push for access to contraception and abortion to be stipulated in law and supported systemically. This is the only thing that will allow women to free themselves from their fears.

Second stop – childbirth

Black and white photographs adorn the walls of the corridors of the maternity ward at Tromsø University Hospital in northern Norway. A photographer has captured the touching moments of childbirth here, next to photographs midwives have hung . In addition to photographs, the midwives have hung an embroidered tapestry – a calendar. There they mark how many babies were born on a given day – pink pins are girls, blue pins are boys. Yesterday, six. Today, none so far. The delivery rooms are simply and functionally equipped: a bed, a bathtub, a medicine cupboard, a ball, a neonatal resuscitation station.

‘May I be frank? We have similar birthing rooms in Poland,’ says Margo Sikora-Borecka from Childbirth with Dignity Foundation (Fundacja Rodzić po Ludzku). ‘Some are even nicer. Maybe except for the fact that in Poland walls are adorned mostly with posters advertising medicines or supplements instead of with art.’

What really impressed her in Tromsø was not how the hospital was equipped, but the stories told by two midwives – Katrina and Martha. They are nice, calm and professional. They don’t call those who are giving birth ”patients”, instead simply ”women”. Bringing a child into this world is a natural process and a social event, it doesn’t turn a woman into a patient even if the medical world needs to intervene. The midwives stress that during delivery they want to maintain contact with the woman above all else, they watch her and listen to what she says. They try to understand what she needs and respect it. According to Margo, a woman giving birth in Poland is usually ”a patient”. And „a petitioner”, typically apologetic for actually having to use the hospital’s services.

‘I have the impression that here the woman giving birth is at the centre of events, not procedures,’ she emphasizes. ‘Medicine serves her, not the other way around.

She also likes the strong position of midwives in the hospital; they are pretty much equal to doctors. Both groups exchange information, take decisions together. The wellbeing of midwives is a priority here, because they are at the frontline of childbirth. In the hospital in Tromsø there are four birthing rooms (a fifth one is being prepared) and five midwifes per shift (one answers phone calls). They work 35 hours a week, have one night shift, and this professional hygiene is very much observed. Midwives can also receive psychological counselling if they need it. In Poland, on the other hand, although there is a good education system for midwives, their knowledge and experience is not appreciated in hospitals. Doctors always have the greatest say. Although midwifery is a profession of public trust, does that affect how midwives are treated? Women are exhausted and often have to work in several places. A primary care midwife who goes to visit a woman after giving birth gets 34.30 zloty per visit. During the pandemic, she also had to buy a protective outfit herself, which then cost more. Midwives are often women with a vocation and a mission, but the lack of money and the constant unappreciation of the work cause professional burnout.

‘So I have mixed feelings after my visit to the hospital in Tromsø,’ concludes Margo Sikora-Borecka. ‘On the one hand, I am delighted to see how an equal society functions, in which people respect each other, and how this translates into the cooperation of the medical staff and the care over the woman and her child. On the other hand, I feel sad because I see how much there is still to be done in Poland.’

The Childbirth with Dignity Foundation has operated for 28 years. It started with the formulation of the ‘Decalogue of Human Childbirth’ and now focuses on advocacy and intervention work. Margo has worked at the foundation for five years. Before that, she was a doula for eighteen years. Women or couples hired her to accompany them during childbirth. She did her best to make it the best experience possible. Often her very presence had an effect on the staff who tried to treat the birthing woman well. Over time, however, she began to feel the need to have more of an impact on the system. In 2019, she took a job at the foundation.

‘In Poland, we have a very well-written law, namely the regulation on organizational standards for perinatal care,’ Sikora-Borecka points out. ‘The problem is that in practice it does not always function.’

For example, according to the law, women have access to epidural anaesthesia, but in reality it is available in very few hospitals. There is no money to employ an anaesthetist in the maternity ward. The standards also stipulate that a woman has the right to submit a birth plan to the staff – a document in which she describes how she envisages a good birth. She can indicate in it, for example, that she wants perineal protection. The medical staff is obliged to read this plan and, as far as possible, follow it. But this can vary, sometimes old habits win.

Unfortunately, reports of obstetric violence by staff also continue to occur. For example, a doctor making degrading comments about a woman’s obstetric situation and people in the corridor hearing this. Or of a midwife shouting at a woman in labour or even shoving, pushing or slapping her. There were instances of a woman’s legs being tied to the gynaecology chair. Or stories of women lying in the ward having to take off their panties and queue up while waiting for the doctor’s rounds. These are occasional incidents, but they should never happen.

So the Childbirth with Dignity Foundation has developed tools to collect data on the conditions in which women give birth in Poland. Every maternity hospital provides information about the conditions of childbirth on the website gdzierodzic.info. Data also comes down from anonymous questionnaires, Voice of Mothers (Głos Matek), which women fill in after their stay in a particular hospital. The survey has over 140 questions. Sometimes the information from the facility and from the mothers differs dramatically. Based on this data, pregnant women can choose the hospital where they will give birth.

In Norway, a woman receives a similar level of care in each hospital. In Poland, the differences are considerable. There are hospitals that receive 80 points out of 100 in the “Voice of Mothers” ranking. There are also those which receive 50. Therefore childbirth tourism is blooming in Poland. Women are capable of traveling 300 km to a hospital in order to give birth in a place where they will be treated with respect.

‘Ranking of the hospitals is our greatest weapon,’ Małgorzata Sikora-Borecka explains. ‘There are no stronger words than those of a woman who has experienced mistreatment during childbirth.’

If a woman feels that her rights have been violated during delivery, she may submit a complaint using the foundation’s complaint generator. The complaint is sent to the hospital. The woman may send it also to the Ombudsman for Patients with a cc to the Foundation.

Because the foundation carries out interventions as well. All over Poland there are Childbirth with Dignity Watchdogs, who, based on reports, catch irregularities. If there are a lot of them in a particular hospital, they jointly decide to intervene. They let the management know what is not working and expect a declaration as to when it will be corrected. In recent months, hospitals have also started to report to the foundation themselves. They see that something is not working well and want to find out what they can improve.

At the same time, the foundation also supports good practices. There is a generator for thanking midwifes on the website. Women who are satisfied with the care received can express their gratitude. Once a year, the foundation awards the “Childbirth with Dignity Angel” title. The chapter chooses winners based on the comments from women who gave birth. Margo was moved the most by a comment from a woman who was accompanied by a midwife during stillbirth. In her difficult experience the woman remembered the midwife’s care, tenderness and authenticity.

Margo points out that Poland had only 272,000 children born in 2023. This is the lowest number since 1945. There is a hypothesis that women do not feel safe and consciously choose not to give birth. Margo hopes that this will send a motivating signal to hospitals to reach out to women. She emphasizes, however, that solutions need to be systemic – including decent salaries for midwives for a start. The burden of responsibility for the quality of childbirth cannot lie solely on individual hospitals and midwives.

Third stop – breastfeeding

At Oslo University Hospital we are welcomed by Anne Grovslien, lactation consultant and manager of the local Breastmilk Bank. She tells us that since 1942, when the first such bank was established in Norway, they still use fresh milk from donors, while in the majority of other countries it is pasteurized. There is a bit of a hassle with raw milk, because each sample needs to be tested, but in exchange it is richer in protein and vitamins. The majority of premature or ill babies receive fresh milk from the bank. Breastfeeding is the norm and an important value in Norway.

‘The society is educated,’ emphasizes Anne. ‘Over 99 % of women make the attempt to breastfeed, and the vast majority continue.’

Women in Norway can freely breastfeed their children in public without fear of facing unpleasant comments. Rather, it is bottle-feeding that is frowned upon. You might think it’s a cultural difference, but Anne Grovslien sees it differently.

‘It’s a political decision,’ she says firmly. A lot depends on whether breastfeeding is supported by state and individual facility policies.

In Norway, it definitely is. Most hospitals are Baby Friendly Hospitals, which means that they promote breastfeeding and follow the World Health Organization’s Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding. Step 2: “Ensure that staff have sufficient knowledge, competence and skills to support breastfeeding.” Step 6: “Do not provide breastfed newborns any food or fluids other than breast milk, unless medically indicated.” In Norway, these rules are also included in national guidelines.

This made an impression on Katarzyna Kołodziejczyk, president of the LittleMammal Association. In Poland, only 23 hospitals have the child-friendly title – 6.8 %. This title is often an additional burden for the staff, as compliance with the standards has to be monitored, staff have to be trained, and there is a constant shortage of staff and money.

When Katarzyna was pregnant, she took part in a two-hour paid webinar on breastfeeding. That is where she heard that the World Health Organization recommends exclusively breastfeeding for the first six months of a baby’s life, and then continuing breastfeeding while introducing appropriate complementary foods for two years or even longer. This was a discovery for her. No one from the national health service had told her about this.

She remarked that she was no exception – the level of knowledge on this subject among women is generally quite low. They usually don’t know that it is possible to breastfeed for more than six months. She decided to attend a breastfeeding promoter course. She met other mothers for whom this was important and who wanted to spread the word. They started cooperating with the Breast Milk Bank in Toruń on a project to collect milk samples for testing. It turned out that the milk of mothers who had been breastfeeding for more than a year was richer in proteins and in antibodies.

She started to search for more effective ways to reach women in order to disseminate knowledge. Hence, she founded the social organization ‘LittleMammal’ (Małyssak). Why the name? When Katarzyna first saw her daughter latched on to her breast, she thought: “Such a little mammal”. They began to take action. They created breastfeeding-friendly zones at local outdoor events. They invited women to sit in comfortable chairs and quietly feed their babies. They organized educational meetings for mothers, support groups. Because sometimes feeding difficulties aggravate women’s mental state, the baby cries and they get frustrated. During the pandemic, they also started running educational webinars about breastfeeding.

Eventually, they dreamt of changes in the organization of lactation care in Poland. They knew from their own experience that it was insufficient. Women often have to look for information on their own, pay out of their own pockets for consultations.

They started monitoring lactation care. They invited women to participate in a survey. They also conducted in-depth interviews with many. At the end of last year, the ‘Lactation Care Monitoring Report’ was published, which revealed some important issues.

Firstly, almost half of the materials that women receive from community midwives are marketing materials – advertisements for formula, their samples or feeding bottles. Sometimes midwives take these materials from representatives in good faith because they want to give something to the woman. And sometimes it can be a collaboration based on benefits for the staff. In both cases, this constitutes a conflict of interest in relation to the promotion, protection and support of breastfeeding. If a woman is given the right support for breastfeeding, she may not actually use the bottle. There are midwives or doctors who prepare their own materials that do not have company logos on them, but more often the woman herself has to search for reliable information.

Secondly, the skin-to-skin contact between mother and baby is too short. The proximity of the baby causes a rise in oxytocin, which is responsible for the flow of milk. The baby touches the breast with his hand and this causes an influx of colostrum. It is important that this contact lasts two hours and should not be rushed. Also after a C-section, even while still in the operating theatre. Meanwhile, the report shows that for more than 30 % of the women it was interrupted as soon as after a few minutes. Babies were taken away to be weighed, measured, Apgar scale scores assessed. Sometimes they were handed over already dressed. It is important to educate the ward management to appreciate the value of this contact.

Finally, the report shows that more than half of the babies were fed formula in hospital – about 30% after a natural birth and up to 60% after a C-section. Women are told: “You don’t have any milk yet” (and yet heavy flows of milk only appear on the second or third day after birth!) or “You won’t be able to feed with this” (and yet women can feed regardless of the shape of the nipples, but it is worth consulting someone who knows about lactation).

All these situations are unthinkable in Norway.

‘We have to convince decision makers that they need to take a serious approach to the implementation of the Baby Friendly Hospital initiative in our country,’ emphasizes Katarzyna. ‘Poland has signed the Innocenti declaration about promoting breastfeeding the same year as did Norway. The team which implemented the initiative in Norway is now part of governmental structures, while in Poland we have the Committee for Breastfeeding Promotion, which is a social organization and is not state-financed. The government needs to take a decision about supporting breastfeeding.

This is why the LittleMammal association encourages everyone to sign a petition on the improvement of lactation care in Poland.

First point: “Establishment of a national program for the protection, promotion and support of breastfeeding with the provision of an adequate budget, the appointment of a coordinating body and its coordinator.”

However, Katarzyna Kołodziejczyk remarks that there are also some good solutions in Poland that are worth promoting. Under the National Health Fund, women can benefit from antenatal education provided by community midwives from the 21st week of pregnancy. This can include up to 26 meetings. Midwives usually invite pregnant mothers from the local area once a week. According to a report by LittleMammal, almost 40% of women took part in this education. However, some women would hear that the midwife would come after birth, so there is still room for improvement. In Poland there are also more home visits after delivery. In Norway, there is one scheduled, in our country as many as six. The midwife can help the woman assess indicators of successful feeding, show her comfortable positions when she is at home.

The visit to the Oslo hospital strengthened Katarzyna Kolodziejczyk’s conviction that systemic solutions should be fought for. “Supporting breastfeeding is a political decision” – these words by Anne Grovslien will stay with her for a long time.

A similar reflection runs through the closing meeting of the visit. In Poland, it is the employees of social organizations who carry the burden of educating and helping women in difficult situations. They provide information on how to get an abortion, they intervene when women’s rights are violated during births in hospitals, they spread knowledge about contraception or breastfeeding. It is high time that at least part of this burden is taken on by the state – both through well-written laws and the enforcement of standards.

The visit to Norway took place in April 2024 and was organized as part of the Active Citizens Fund – National programme. It was attended by four representatives of Czech social organizations, who will organize a similar visit to the Czech Republic for Polish women in September 2024.

Text: Urszula Jabłońska

The report was published on Onet.pl