They are sometimes referred to as “people in transit”, although essentially everyone comes into the world somewhere and has to die somewhere – usually in a different place to where they were born. They travel a number of roads in the course of their life, make certain decisions, meet people, part ways with people. Sometimes they come to a perfect place, persistently promoted in American movies, while usually they are continually on the move, and always striving for something. However, it has become customary to call people in transit refugees – people who went to foreign countries, where the reality is entwined with a foreign language, into the great unknown. They cannot all be branded the same, as “migrants”, because each has their own motives for their journey, dealing with their own memories. Due to fate or providence, these people found themselves in Poland, often not even knowing that such a country existed when they set out on their travels.

On occasion, lawyer Katarzyna Przybysławska checks Tik Tok to see what falsehoods traffickers feed their customers. – Sometimes they spread a wide variety of nonsense. For example, they portray the Polish-Belarusian border as the Belarusian-German border. They are often told things like: when you cross the border into any Schengen country, at that point no one in Europe will throw you out, and you will be able to travel anywhere you wish with ease, because there are no border controls.

Przybysławska is one the founders of the Halina Nieć Centrum Pomocy Prawnej (Legal Aid Centre) – an organisation that provides pro bono legal advice to persons such as refugees, including victims of human trafficking.

A few years ago, this association was awarded grants under the Active Citizens Fund – National Programme, in which an e-learning course was produced on Identifying Foreign Victims of Abuse and Torture, and Border Guard employees were also given training on this subject. They are the first Poles encountered by people who are migrating.

The problem is that since 2021, Poland has been pursuing a policy of push-back on its borders. In other words, if officers come across foreigners in the forest near the Belarusian border, and they request international protection, these foreigners are usually pushed back to Belarus. There is no room for observing, or asking, whether a particular person has suffered abuse. Usually, only when a foreigner is encountered who is in serious condition does that person have a chance of being taken to hospital in Poland and to a secure facility.

Waiting room

There are six secure facilities for foreigners operating in Poland – in Białystok, Kętrzyn, Przemyśl, Krośno Odrzańskie, Biała Podlaska, and Lesznowola. They are operated by the Border Guard. They are not a prison, but it is hard to think of these places in any other way. They are surrounded by a wall with barbed wire on the top, and order is maintained by uniformed offers. There are specified times for eating, going for a walk, and sleeping, while above all there is the great uncertainty; The refugees placed there have no idea what awaits them and how long they will be there. Those who hold the record have spent as long as two years locked up. During this time, they can only be visited by lawyers or family (living for example in Yemen, Eritrea, Iraq, or even Cameroon). At times, people from CSOs are also able to gain access. – People there are not allowed to use telephones that have a camera. They are only allowed to have a Nokia 105 – says Joanna Sarnecka of the Fundacja na Rzecz Kultury „Walizka” (Foundation for Culture “The Suitcase”), who travels from Podlasie to the Przemyśl facility regularly. She makes appointments for meetings, but while in fact it is permitted for meetings to last up to ninety minutes, sometimes the officers announce that the meeting is over after fifteen minutes. Sarnecka is not allowed a smart phone when visiting, which means that if the refugee does not speak English, as a rule a conversation is not possible. They communicate by drawing on a piece of paper, singing songs from their country, learning their native languages. What is the purpose of all this? To make a person who is locked up feel that they mean something to somebody. That someone knows their name and knows that they exist.

– In Przemyśl, a boy from Iraq was suffering from shortness of breath at night – a chronic illness that requires an oxygen mask to be worn at night. He had an official diagnosis and recommendations for oxygen therapy, but this was not respected. The boy lived in a room for eight persons, and had a number of attacks of breathlessness every night. I proposed that my foundation would provide treatment, but was told by the facility’s authorities that this would not be necessary – Sarnecka continues. – One time, his fellow inhabitants in the room called me during the night and said that he was having a particularly serious attack. I called for an ambulance, and a doctor was allowed to attend to the boy for a moment. After that, it was communicated to me, through his fellow inhabitants, that if I called for an ambulance again, the boy would be placed in isolation, and then no one would know anything about what was happening to him – she adds sadly. – a taser was used in the case of another boy, a boy from Sudan, for spending too long eating in the canteen.

On the other hand, Urszula Wolfram from the Podlaskie Ochotnicze Pogotowie Humanitarne (Podlaskie Voluntary Humanitarian Emergency Service) visits the Białystok secure facility regularly: – Even a brief visit to a place like that is truly devastating psychologically for these people. Above all they are numbers – instead of first names and surnames they have ID numbers. One refugee thought that the word kurwa (fucking) in Polish meant “good morning”, because they are greeted by some with the phrase “k..wa, śniadanie” (fucking breakfast).

Rape is not talked about openly

When a foreigner is placed in a facility of that kind, it is referred to as administrative detention. Human rights lawyers agree that administrative detention is misused in Poland. This is especially true because if there is reason to believe that a foreigner has suffered abuse in the past, under Polish law that person can never be placed in a secure facility. – Placement in detention is not a punishment for crossing the border illegally, it is only intended as a precautionary measure in proceedings. Therefore, if there is a risk that the foreigner will not cooperate and that they will abscond, and the person needs to be identified for the purpose of the case, they can be detained. The issue is however that the law provides for less stringent security measures for a case of that kind – known as alternative measures, such as being required to report to a police station regularly, surrendering their passport, or leaving a deposit of a certain amount of money. In our view, however, these measures are not used often enough. Despite being a last resort and depriving people of their liberty, detention is the first choice in rulings –– Katarzyna Przybysławska says.

– It is not easy spending time in a detention centre – says Beata Zadumińska, a psychotherapist who works with people who experience trauma. She also works with the Halina Nieć Legal Aid Centre, she is the person who trained Border Guard employees. – In facilities of that kind, it is easy to lose a sense of elementary control over your life. This can be described as border status that lasts indefinitely: anything could happen, we have no control over anything, and this situation can go on and on. In psychological terms, being in this form of suspension is one of the most destructive events, as it can trigger a feeling of protracted helplessness, and apathy, and this reduces further an emigrant’s capacity for managing in their new, and often completely unfamiliar situation.

Employees at the Halina Nieć Legal Aid Centre examined 366 files at the Biała Podlaska, Przemyśl, and Białystok Regional Courts. Many cases of detention of foreigners were in fact handled by these courts. The file examination findings? It was found that there was a high instance of cases of people whose mental and physical state suggested that they been abused, and were placed in detention despite this. In many cases, this was prolonged detention. Even in the dispassionate court files, information given by a foreigner could be found that should at least raise the suspicion that they might have been abused. People who have had traumatic experiences are often inhibited when it comes to giving details, making it very hard, objectively, to identify victims of abuse. Meanwhile, the Polish authorities have an obligation to take all measures to investigate the essential circumstances of every case – Przybysławska says. The organisation’s lawyers travel to a number of secure facilities to provide legal advice. – I myself was faced with a situation in which a woman only admitted that she had been raped repeatedly at one of a number of meetings. This is not something you say straight away.

Even if someone carrying traumatic baggage from the past is placed in a facility, someone should notice that something is wrong, for example that they wake up screaming in the night, are afraid of others, practice self-mutilation, and suffer from anxiety. All of this might indicate post-traumatic stress, or shadow of trauma – even if not verbalised. The problem is however that there is insufficient psychological aid at secure facilities. Rashid experienced this. He fled Chechnya with his wife and two small children. He was in possession of documents proving that he had been beaten by police in Russia, but he and the entire family were placed in a secure facility. The parent was concerned about the behaviour of the elder son, who was talking to himself, often cried for no reason, and became hyperactive. Rashid requested a consultation with a psychologist to explain what they had been through as a family. This had little effect, because the psychologist knew so little Russian that in fact it was not possible to communicate. These people were locked up for nearly six months, although they should never have been placed there.

Ping-pong

Dara left Iran with his brother. Both are Christians, and fled due to persecution by Islamic radicals. They had a reason, and proof, and hoped to be granted international protection in Europe. They crossed the Belarusian-Polish border and were met by the Border Guard. The officers were not interested in their story, and the boys were simply pushed back to Belarus. – the Belarusians did not let us come back, and told us to go to Poland, and so we went. The Poles caught us and pushed us back to Belarus. and this kept happening. We attempted to cross the border nine times. We did not understand what was happening – Dara says in English. He does not know that human rights activists refer to the moving of refugees from one country to another as human ping-pong. The eighth time, the brothers walked many kilometres through the forest deep into Poland and decided to go to the police. – We thought that maybe the police would listen to us, but they called the Border Guard, and once again we were taken back to the other side – Dara continues. For this reason, the two brothers planned to try to get to Germany next time, in the hope that there they would be able to tell their story. They were caught one hundred metres away from the German border, and this time they were placed in a secure facility. Initially, this was for three months, and then they were transferred to the next facility, where they spent three months, and then to the next one. And again – three. In total, they were locked up for nine months. At one of the facilities, they learned that a Instytut na Rzecz Państwa Prawa (Rule of Law Institute Foundation) lawyer, Tomasz Sieniow, gave pro bono legal advice. He became their representative, and the two men were able to be moved to an open facility, where they are free to come and go. Today, the brothers have all the required documents to live and work in Warsaw legally. Dara works at a kebab shop, and his brother at a Greek restaurant. – I am an engineer, I had my own business in Iran. I would like to start a business here, too. In the autumn, I am going to Łódź to attend an intensive Polish language course.

A sort of happy ending

Tomasz Sieniow started assisting refugees due to the huge impact that a meeting with a Chechen woman many years ago had on him. – She was a single mother with three children. She had been through a lot, but had managed to escape from Russia. She worked as a teacher in a Polish school, but unfortunately she got into a car accident and fell into a coma. At that time her children disappeared from the facility – and after some time were “found” with relatives in Belgium. Initially, she was shunned by the Chechen community because she had been in the car with the head teacher, and in that culture a woman cannot travel in a car with a man other than her husband. For ten years I visited her in hospitals, and then in a care home. She was bedridden after the accident, but fortunately was not fully aware of what was happening to her. When you came to see her, she would say cheerfully: “Everything is fine with me, the children have just been to see me”, when in fact I think this was her body’s way of protecting itself against losing her mind completely due to suffering and loneliness – Sieniow says. He adds that for him this story does have a kind of happy ending. – Ten years later the children – who had grown up by that time – found her, and one of them took her to live with them in Germany. We obtained all of the necessary documents, and now they are together.

Fundacja Instytut na Rzecz Państwa Prawa is a CSO in which the employees provide for instance pro bono legal advice to foreigners. Due to being awarded grants under the Active Citizens Fund – National Programme, the foundation conducted a project “Migrants Have the Right to Have Rights”, helping 281 people locked up in secure facilities. The lawyers represented foreigners in court and attempted to reduce the time spent in detention, and subsequently sought compensation for wrongful detention, i.e. in everyday language, to sue Poland. – I think that the encounter with Poland is very painful for many people seeking international protection. Once they leave the secure facility, they usually want to have nothing to do with Poland, saying: “Polska did us harm, Tomasz. We cannot stay here” – Sieniow says. – For us the greatest success was when courts in Lublin, overseeing the facility in Biała Podlaska, began releasing foreigners after three months of detention, in light of the tardiness of the activities performed by the state. That was a breakthrough.

According to Border Guard figures, in 2021, when the Polish-Belarusian border crisis began, there was a record number of people in secure facilities, of 4052, of which 567 were children. – The most difficult thing was probably dealing with their crying, and on top of that the suffering of pregnant women, and miscarriages… The sight of the exercise yard in Krośno Odrzańskie is always also upsetting – Sieniow thinks for a moment and gives an account of a Kurdish family that the tried to help: – they had been detained for six months, and had no idea what Poland would do with them or what their rights were. When an attempt was made to deport them, the mother jumped from the aeroplane boarding stairs and twisted her ankle. They went back to the facility and were constantly told that they would be deported again, but it was unclear when. Their twelve-year-old daughter found it unbearable and after a few months attempted to commit suicide by hanging herself on a towel. After that she was taken to a psychiatric hospital for one day. She was in the corridor, watched by a Border Guard officer, but the doctor recorded that she integrated with other children and took part in therapeutic activities – the lawyer recalls.

When Sieniow was able to get the family released from the Biała Podlaska facility, the first thing he did was to take all of the children for ice cream. That was two years ago. The family now lives in London. Sieniow visited them recently, and this time, they invited him for a kebab.

Give a hug, if you can

A country can infuse dislike and fear of refugees in citizens by objectifying people who enter Europe illegally. By using them to instil fear. Calling them a “wave”, “flood”, and “weapon in the hybrid war”. – It is illegal to cross the border at a point where this is not permitted, In the same way as crossing the road when the light is red or parking where prohibited. However, if the police used physical violence against people for crossing the road where it is prohibited, there would be an uproar – Mateusz Krępa says, who is writing his doctoral thesis on organisations that help migrants, and a member of the group “Badacze i badaczki na granicy” (Researchers on the Border). He was asked by the Stowarzyszenie Interwencji Prawnej (Legal Intervention Association) to write a paper on “Treatment of People Migrating on the Polish-Belarusian Border as Institutional Abuse”, part of the report “Come out of the Shadows. Help for Victims of Hate” financed under the Active Citizens Fund – National Programme. – Crossing the border illegally is not a major crime, but politicians have adopted the line that as a country we are under threat for this reason. The abuse of refugees – whether due to duration of detention, or push-back alone of unarmed people – has become acceptable. Imagine the scene when someone is pushed back across the border… – he adds.

In November last year, both Mateusz Krępa, and representatives of Stowarzyszenie Interwencji Prawnej talked about this at the conference “CSOs at the forefront of refugees support – common challenges and solutions” in Warsaw, at which approximately one hundred speakers from eleven countries shared know-how on working with refugees and the situation of people in transit who ended up in their countries.

What is the first encounter with Poland like? It varies. People working for CSOs hear accounts from refugees of border guard officers who provide food and water, but also of those who destroyed their telephones, ridiculed them, threatened them with a weapon, and shouted at them. More or less what is shown in Agnieszka Holland’s film “Zielona Granica” (Green Border). – As a voluntary worker, I travelled around Podlasie providing help in an open facility. When an Iraqi woman discovered that I did not have accommodation in Białystok, she suggested that I stay with her in her room. At the facility, I met women who had crossed the border. I cannot put their screaming, and their stories out of my mind. One was thrown onto wire and had cuts on her body. She was taken to hospital in Poland, but her husband and four-year-old son were taken back to the forest, to Belarus. She didn’t know if they were still alive and could not contact them. She was screaming with despair and loneliness – Judyta Sowa recalls. She also helped a Kurdish family at the facility, a father and five children. The mother had not survived the journey. She died in a Polish hospital when she was pregnant with their next child. She was buried in Podlasie. – I formed a relationship with that family. The children would come up to me to hug me. When the youngest had a hug he would have convulsions, being thrown around on the bed. I asked a friend who was a psychologist what to do. It transpired that this was his way of dealing with the trauma caused by being in the forest and the death of his mum. Because he trusted me, I could bear that and could continue hugging him. So he would come to me, have those convulsions, and we would doze off like that – Sowa says.

Shadow

Hate begins in an innocent way, for example with a joke about skin colour or a widespread stereotype. – We allow ourselves to make jokes and be spiteful. This fosters a dislike for other people, but at what point does abuse start? Is it that one smack given to a child does not constitute abuse, but beating a child to a pulp does? And maybe only the second time? – Agnieszka Kwaśniewska-Sadkowska, a Stowarzyszenie Interwencji Prawnej lawyer, raises these questions rhetorically.

Ticket inspectors on a tram told citizens of Belarus to “go back to Lukashenko”.

When talking on the street about where he was from, a man from Iran was hit in the face and told “Irak, Iran, all the Muslim, we will kill you”.

A pregnant was beaten and told to “fuck off to Ukraine”.

A Ukraine citizen was hit on the head on the street and pulled into a nearby pub. The security guard asked the assailant what was going on. When he heard the answer that the person was “a Ukrainian whore”, he joined in in kicking the person.

This happened in Poland. Each of these events was an act of abuse, but not only. It was abuse on the grounds of nationality, in other words a hate crime.

Stowarzyszenie Interwencji Prawnej, Stowarzyszenie Nomada, and Stowarzyszenie Homo Faber – which have been providing help for people in transit for years – worked collaboratively on the project “Coming out of the Shadows. Helping those who are victims of hate”. They wanted to help foreigners who had experienced abuse in Poland for being different. It was found however that it was difficult to convince a victim not to sweep the crime under the carpet. – Usually, foreigners swarm into our office. They know that they can get legal advice and aid here, with regard to obtaining all of the documents relating to residence in Poland – Kwaśniewska-Sadkowska says. She was sure that when the organisation announced that it would represent refugees who were victims of hate crimes, there would also be a lot of interest, but she was wrong. It was difficult to convince victims to have faith in Polish law and agree to open old wounds, and to have painful experiences divulged. They preferred to forget painful events, and say nothing. – We argued that it was not worth it to dismiss this, that they had to fight for what was theirs. Foreigners are scared to go to the police for the same reason that women are unwilling to report rape. You never know what kind of officer you are going to encounter. Whether they will say “you’ve only got yourself to blame”, or take the case seriously. We provided support for those people, for example by going with them to the police station and not allowing a police offer to be dismissive towards a foreigner. Sometimes a complaint had to be made to a court due to a case being closed. You had to be stubborn and put your foot down. But above all tell the victim that they had not done anything wrong – Kwaśniewska-Sadkowska adds.

During the project, the lawyers analysed 43 cases concerning insulting behaviour, threats, and beatings. Statistics were compiled and a report was produced. – The Ministry of Justice is working to ensure that hate crimes have a more prominent place in the Criminal Code, so we will also submit our document. In fact, we explained to foreigners that if no one reports the crimes, then no there are no proceedings, and crimes related to race, religion, or for example nationality are not included in the statistics, that Poland is heaven for foreigners.

Three years in transit

It is not the case that Poland has a poor reputation among all refugees and they all want to forget about Poland. Thousands of people from Ukraine have experienced warmth and kindness in Poland. – When people started coming over from Ukraine, the line adopted by some elements of the media was that they were war refugees, to show that those coming through the forest from Belarus were not war refugees, i.e. they were not genuine. The message conveyed to the world was that a genuine refugee is someone who flees a country in which there is armed conflict at a particular time. But this is not true – Katarzyna Przybysławska of the Halina Nieć Legal Aid Centre says. International law does not make this distinction. A person only has to have reason to fear that they would be persecuted in their home country. – Of course, there are often cases in which a person who is persecuted in their home country also has financial problems and comes to Europe seeking protection and at the same time hopes to improve their financial standing. One does not exclude the other – she adds.

But there are also cases of people who travel from distant countries, through a number of countries, until they get to Poland, and determine that they do not wish to go any further. That they met good people, that this place is enough, even if perhaps there are better and more beautiful places. – I did not know that adults can play with children and that a mum can show feelings. It wasn’t like that in our country – twenty-year-old Józef from Afghanistan says, speaking Polish. He chose his forename for himself and that is how he wants to see himself.

He left home when he was twelve, still a child, although he no longer felt like a child. – I would spend whole days with friends on the street, and I considered that normal. At home you ate, slept, and prayed. I did not have a good relationship with my mum. When I was eleven, she gave me a severe beating with a vacuum cleaner power lead, and shouted “get out of this house and never come back”. That was the first time that I thought: “God, what am I living for? I don’t want to any more” – he recalls.

If you are born in a country like Afghanistan and want to leave the country, for most citizens that simply cannot be done legally. That means you have to have money and contact with traffickers, and have knowledge of a network sometimes covering dozens of countries. Józef was determined to leave – like nine of his friends. The boys were sent to Europe by their families in the hope that they would get there, find a job, and keep their relatives in Afghanistan. His father arranged everything for him, but told him: “On the way you will find hunger and death. Remember: do not call us” – he says. It took three years to get to Poland. Józef first realised that his father had been right when he was in the mountains, somewhere between Pakistan and Iran. – We walked for three days and two nights, in the wind, and dust. In those conditions, friends stopped being friends, by that time everyone was only thinking about themselves. When the traffickers sent a number of mopeds to get them, it turned out that they were one place short. My friends got on and left me behind.

At sixteen, I went to school

People travelling when migrating get to know people in similar situations. They exchange information and contact details. Sometimes someone shares their water, while someone else charges money. Those who are slower or crippled are often separate from the group, cannot keep up, and in effect fall behind. Józef met people like that in the mountains. Him – a lonely twelve-year-old boy. – We agreed that we would go together. There were four of them on a single moped. I was at the back. I was exhausted, my eyes kept closing, and I didn’t even notice my leg getting in the chain. My leg was cut down to the bone. I fell on the ground and was bleeding. The person driving kicked me and rode off with the rest. Then I met someone who saw my leg and said: “Boy, you are dying!” He had a very long scarf, which he cut into pieces and used to bandage my leg. We reached Iran together – he says. He got into contact with his family and a trafficking network. He found a doctor and had an operation. He stayed in Iran for a few months, and when his leg was in fairly good condition he found a job making plaster panels. Next, he went to Turkey and worked there as well. – He tried to get into Bulgaria fifteen times, but was unable to. It is from there that I have the worse memories. The Bulgarian Border Guard were sadistic, they set dogs on us. One time they ordered us to strip down to our underpants, and kneel with our arms above our heads, and gave us electric shocks. They burnt all of our clothes and backpacks, right in front of us. The deported us to Turkey wearing only our underpants, and were laughing the whole time, he continues the story.

He only managed to get into Bulgaria when a trafficker bribed the Border Guard, which arranged by itself a bus for a group of refugees to continue their journey. Later on, they were transferred to an HGV. – We were in there a few days, scared to move. We soon ran out of water. Luckily, I had with me a screwdriver and masking tape. When it rained, I made a hole in the tarpaulin cover and we drank the water. At a certain point I thought I could not take it anymore, and that I would die. I cut open the tarpaulin cover and got out, and found that we were in Terespol. I didn’t speak Polish. I walked up to some drivers and begged for water, communicating using hand gestures. I pointed to my mouth and was given a lot of water – I drank, and drank, and drank. Then the police came and handcuffed me and my friends.

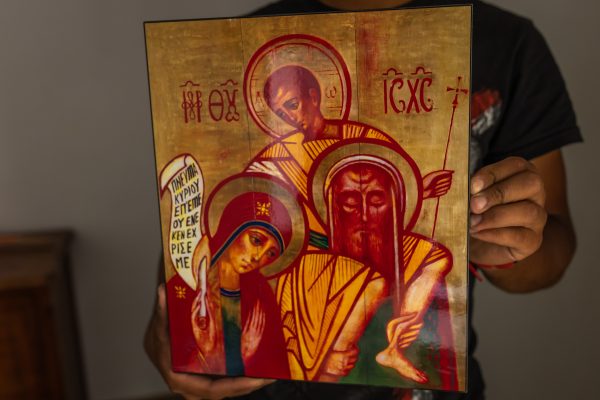

With a peer, he was placed in family children’s home near Lublin. Tomasz Sieniow from the Instytut na Rzecz Państwa Prawa was assigned to be their case officer, because they were minors. When Józef’s friend fled to Germany, he was left in Poland alone. He did not speak English. The foster mother turned out to be open, and at one time had had Chechen children stay at her house. She knew that a smile and post-it notes with words in Polish would help with communication. One time he even went with her to church. – She never tried to convince me to do that. She said that on Epiphany, a Muslim can go to Jesus. I went and I was terrified, because all of those pictures were looking at me! What a horrible place – I thought. When I told the story in the evening, mum laughed a lot and explained that religious pictures are painted that way to make it easier to focus on prayer – Józef says cheerfully.

At sixteen, he joined the first year at school in Poland. He poses in pride for the end-of-year photos with his seven-year-old fellow pupils. He studied a lot, and, instead of the second year, went straight to the fourth year. That was the end of his school education. By that time he was an adult and had to go to work. At that point, his friends tried to convince him to go to Germany, and so he went to his foster mother for advice. He asked whether he could be in Poland completely legally and whether there was work in Poland. I answered “yes” both times.

And so he stayed. He rents a flat in Lublin, and has a job. He talks to his biological parents once a week, and sends them money. The distance between them is 5 000 kilometres, and at that distance their relationship is better than ever before. Józef simply calls his foster mother “mum”. He dreams of becoming a Pole. “Here, from Mum, I discovered what love is”.

The Projects „Improved identification of foreigners who are victims of torture and abuse” run by Halina Nieć Legal Aid Center, „Migrants have right to have rights!” run by The Rule of Law Institute Foundation and „Coming out from the shadows. Providing support for victims of hate” run by Association for Legal Intervention were conducted using funds from the Active Citizens Fund – National Programme funded by Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway using EEA funds.

Text: Ewa Wołkanowska-Kołodziej

Photo: Anna Liminowicz

The report was published on Onet.pl