In the human kingdom, define or be defined. Self-advocates of marginalised groups – people with disabilities, their parents, minorities – choose the first option. They want to talk about themselves and their needs, in their own words. Not from the standpoint of a victim, but addressing the substantive issues, stressing the things with which society fails to provide them, and making suggestions as to changes to the system that would improve their lives.

The well-known American psychiatrist Professor Thomas Szasz, who advocated giving people with mental illness freedom and responsibility, has said that in the human kingdom, you can define or be defined. Deciding to talk about your life can be liberating, because you then take control of your life, not only in the sense of being active and taking measures, but also in the symbolic sphere, with regard to a narrative in which you finally find yourself and feel at home.

One of the most important things that various groups that formerly faced exclusion and persecution wish to regain is the right to tell their story in their own words.[1]

The idea of self-advocacy was born in Western Europe in the 1950s. Towards the end of the sixties, the first self-advocacy organisations began to form in Sweden, created by people with intellectual disabilities, who wanted to talk about their needs publicly, and sought a greater role in community life.[2]

In Poland, various marginalised groups have been practising self-advocacy for years, while the function of a self-advocate has only recently entered the mainstream. Protests held by parents of children with disabilities led by Iwona Hartwich, which attained broad media coverage, definitely helped this cause. Iwona Hartwich became an MP in 2019. In December last year, when Monika Horna-Cieślak was appointed Ombudsperson for Children, she appointed seventeen-year-old Jan Gawroński, who has autism, to be her aide for community matters. In 2022, the association Nasz Rzecznik (Our Advocate) was founded, which provides support in various areas of self-advocacy.

This is an activity that is important not only to people with mental illness and disabilities and their parents, but to all groups that are socially marginalised, such as the Roma people, LGBTQ+ community, or people who are refugees. These groups are not seeking to be pitied or viewed as victims, they want to have a say, and rights and opportunities to make decisions about their own lives. I went to Łódź, Kędzierzyn-Koźle and Kraków to listen to them.

You don’t have to do anything

– I remember an amusing moment – Bogusia recalls, and smiles behind fashionable glasses and a perfectly cropped fringe. – I am walking around in a shopping centre and talking to myself. I am saying: you have to force yourself to go shopping, treat yourself, not Tymek, and I continue, saying, excellent, go straight ahead and now turn and go into the cosmetics store. This was a way of learning to take time for myself, and ensure that there is a space in which you don’t have to experience your role, try harder, or wonder how someone perceives you. You simply don’t have to do anything. – She adds: – because a bad conscience, guilt, and shame are definitely a natural part of caring for a dependant.

Are you a mum? You have probably had that feeling many times. Do you feel that it is not right to devote time to yourself and not the children, spending time with a friend, or working, instead of being with them?

Except that Bogusia and mothers like her feel all of that to the power of ten. They feel that when their children are babies, when they go to school, when they grow up, and when they begin to get old, as a child with a disability changes your life forever, and is dependent upon you forever as well.

Free jazz and popcorn on the racing track

Tymek, Bogusia’s son, is lying spreadeagled on a soft, green chair. He is curious about my dictaphone, and reaches out to it. He is slim, with curly blond hair and glasses with blue frames. He loves electronic devices, so his mum gave him a toy that lights up, and eventually a telephone to keep him occupied while we talk.

Tymek is nine and has Angelman syndrome. Bogusia explains that this is a rare genetic condition. In Poland, there are no tests or information about it, which is an added problem for parents – there is no point of reference. In addition, each case is different, and requires a highly personalised approach. This condition results in permanent disability. Due to this condition, Tymek does not speak, and has balance and sensory issues, delayed psychomotor development, stiffness of muscles, and seizures. He can walk on his own, but needs somebody with him at all times – to help him get dressed, give him a glass of warm water, which he likes, and hold it for him. It is also common for people with AS to smile frequently, including when inappropriate, such as when someone is in pain.

Bogusia asks whether she should say more about AS, or rather about Tymek, because for her it is very important to look beyond the symptoms to see a particular boy, a person with a personality and passions. – For example, my son brings a special sensitivity to the world, a sensitivity to sounds and music played on instruments – she says. – Tymek loves going with me to see live free jazz. He communicates what other things and whom he likes, or something he wants, by making gestures and talking using an interactive book. He communicates his choices by sticking pictures of objects into the book using Velcro. We go to the theatre together, and he can sit through an entire performance, and he loves playing with healthy children. Luckily for me, my friends are open towards him. For example, he has a good friend, Gwidon, the son of one of my girlfriends, and that is an excellent relationship. Gwidon does silly things that make Tymek laugh, and both are happy, or Gwidon rolls popcorn down a slide for cars, and Tymek eats it.

– there is one more important aspect to contact with other children – Bogusia says. – They ask me a thousand questions about everything: why doesn’t Tymek talk? Is his condition contagious? Answering their questions is a huge responsibility, because these are the children who one day will construct the world in which my son lives. I hope that when that happens, they don’t remember a poor, disadvantaged boy, but for example they remember that they listened to music together.

A moment of respite

Talking to others about her own experiences and viewpoint comes naturally to Bogusia. Since Tymek came along, she looks at what she can do in life despite her limitations, and what she can’t do, and talks about that openly with others.

For this reason, when Maja Giżycka-Różalska from the Łódź Foundation Ktoś (someone), a foundation that helps parents and carers of children with disabilities, proposed that she become a self-advocate, she did not need convincing.

Bogusia went to Ktoś when she was planning to set up a support group for parents and carers of children with disabilities. She thought that she would invite people who receive help from the foundation. At that time, the main activity of Ktoś was providing a respite service for parents of children of that kind. In the project “O nas z nami” (About us with us) operated thanks to grants under the Active Citizens Fund – National Programme, the foundation helped twenty families by providing respite care free of charge for a few hours a week.

Respite care is still not very well known in Poland, but what is this service? A carer is assigned permanently to the family in question, and comes and takes care of a person with disabilities, or takes them for a walk or to do activities. During this time, a parent who, day by day, is often never away from the child, can take time for themselves. For many people taking part in the project, this was the first time this had happened since they became parents.

At first, Bogusia was visited by a carer for a Ukrainian mother and daughter with autism, whom Bogusia had taken in when the war broke out. – When Julia and Katia left, Magda Kijańska, the founder and president of Ktoś, asked me whether I needed that kind of care – Bogusia recalls. – and suddenly she had a realisation: my word, I didn’t think about myself! It was an unusual time, when I was in the process of recovering and determining my needs, so that was perfect.

Krzysiek was the carer who started coming to take care of Tymek. Bogusia was able to go to yoga or for a long walk, do some meditation, read a book, return to her artistic activities (she studied at the Academy of Fine Arts), or pop out to see an exhibition or to a shopping centre – to do shopping only for herself.

The Ktoś foundation asked parents taking part in the “O nas z nami” project to become self-advocates. Seven mothers, Bogusia among them, agreed.

An empathic community

– to me, a self-advocate is someone who has come up against an obstacle or limitations of some kind, and in this context talks about their own affairs, rights, and ideas on how to function – Bogusia explains. – I think that the key is being aware of your place in society.

At Ktoś workshops, the future self-advocates (only women came forward) learned self-presentation and had classes with a psychologist on inclusive language.

– For example, we learnt how the word upośledzony (impaired) originated. It means gorszy (worse), I was shocked – Bogusia recalls – but for me the most important thing was discovering the way in which we should talk about ourselves. I realised that there was nothing to be gained from talking from the point of view of a victim, because that causes stigmatisation, and does not effect real change. I used to have in my heart this idealised approach: “all of us together have power and we can achieve a lot”. Nowadays, I think that talking about the substantive issues is much more important, to stress the things that families of people with disabilities are not being given and make suggestions about specific changes to the system. This is because the people who manage the system do not always know which solutions are the best and what we truly need. This enables equal opportunities and the creation of a society in which there is care and empathy, and the conviction that people with limitations can enrich that society in different ways to able-bodied people. A little bit like in a family, in which we differ but learn to see each other with compassion and understanding, and function together. I know that this may sound abstract and idealistic, but I believe it.

Having done the workshops, Bogusia has a feeling that she knows what to say at a forum. She has now done this on television and in the press. The workshops also helped her obtain funds for activities important to her. She raised funds to continue the workshops – support groups for parent and carers of children with disabilities. Last year, she and three mothers of children with AS opened the foundation FAST Poland. The main aim of the foundation is to provide assistance to families with people with AS, provide up-to-date information about the condition and treatment, and have medicine supplied if any becomes available.

Ktoś, someone beside you

The Ktoś Foundation itself was created due to awareness of needs and solutions. The founder, Magdalena Kijańska, started with her own experiences and becoming consumed by care of her daughter, who had a disability.

After a long time trying, she got pregnant when she was 39. In the fourth month, she was told by a doctor that the child would have Down syndrome, but after that there were several different diagnoses. Samples taken for genetic tests were sent to the Netherlands, where a more precise diagnosis could be reached. The results ruled out several dozen conditions, but there was an observation – that it could be Zellweger syndrome, which is a rare genetic defect. Children with this syndrome do not live beyond one year. Although Magda’s daughter, Pola, had an Apgar score of nine when she was born, neurological symptoms characteristic of Zellweger syndrome appeared soon after being discharged. She died when she was eleven months old.

– For that period of just under a year, my husband and I barricaded ourselves in at home and were completely focused on taking care of Pola. We did not allow anyone to visit, in case they brought an infection of some kind. The pain and loneliness were immense – Magda Kijańska says. – I returned to that experience in 2018, when I decided to found Ktoś. I chose the name to stress that in difficult times someone to stand by us, give support, and help us is really needed. I thought that there must be other mothers who do not let anyone into their lives, and are alone with their ill children the way I was, and I was not wrong. We knock at their doors and try to convince them to trust someone and let them look after their child for a while, so that they can rest and spend time with people.

We have in our care the mothers of babies, like Bogusia, but also mothers whose children are aged 30-40, usually with cerebral palsy, because there is a long lifespan with that condition. Most of them, like Bogusia and Tymek, are families where there is only the mother. Last year, out of one hundred families for whom we provided help, 98 were single mothers.

Magdalena Kijańska joined in with the measures to devise training for self-advocates, because she had the feeling that too little was still being said about parents of people with disabilities. She had a strong desire for parents to describe in their own words being stuck at home in this way with children, and the role of carers who can relieve them for a while.

– Those mothers live in their own worlds and might not have the strength to tell others what their daily life is like – she explains – Often, they are scared to go beyond their four walls, in case they are judged. One of the Ktoś self-advocates is Marysia, for example – mother to Sebastian, who is 45, and has Hydrocephalus and child cerebral palsy. There is Gosia – mother to two adult sons, of whom one is waiting for a heart and lung transplant, and the other is bedridden due to his pram being hit by a car in childhood. There is Regina, whose son Paweł is now 35, and at 18 lost his short-term memory due to sepsis, and remained at that mental stage of development – Magda Kijańska continues. – Those mothers, aged sixty or seventy, devoted their entire lives to looking after their children. Clearly they have plenty of needs of their own that they never fulfilled. For years, they did not talk about themselves. Bogusia is our youngest self-advocate, and so it happened that we had contrasting viewpoints of two generations. Elderly people are reluctant to leave a child with anyone else, and younger people do not see it as neglect when their child goes to a special kindergarten or daycare centre, for example. They know that if they take care of themselves, it is easier to take care of the child, and life simply becomes better and happier. Saying this aloud conveys an important message not only to other parents of children with disabilities. Who is better placed than they are to tell society about their own needs? A positive approach and nice appearance of self-advocate mothers is also an important message for the world, because people often think that because they have children with disabilities, they should be unkempt, poor, maybe due to problems, and not manage. It is time for this to change!

We are thesameabled

The perspective also changes when talking to adults with disabilities, whom I meet in Kędzierzyn-Koźle at the Różnosprawni (thesameabled) Foundation. It has its offices in a pavilion on a residential estate from the 1980s. We sit at a colourful table made of sheet wood, with artwork on the walls. Probably created by the people who have come to talk to me? Nice – I think to myself, but Mateusz Smołucha, the founder of the foundation, soon brings me down to earth: – I really don’t like it when working with people with disabilities is reduced to artwork that is often more the work of therapists. In fact, please ask our employees what they do here.

He used the term “employees” instead of “people in care” deliberately, because the Fundacja Różnosprawni also has an ZAZ (Zakład Aktywności Zawodowej – employment centre) that employs people with disabilities.

Grzegorz says that he has worked here for five years and usually cleans the stairwells on the Kędzierzyn residential estates. Dawid and Adrian also do cleaning, and in addition urban repairs, for example of roads, and mowing lawns. Maciek does renovations: – I like breaking up furniture and chopping wood – he smiles – I also clean in the vicinity of the ZAZ. Mateusz, sitting next to his girlfriend Martyna, says: – I have been working here for three years. My role is repairing roads, tending to green areas, and sometimes construction.

– I clean stairwells, and also clean our library in the market square – Martyna says. – I like working here and getting to know people. Mateusz and I met at the ZAZ.

Waldemar and Alicja are also a couple, and have been for ten or more years. They have a daughter aged fifteen. They have come to the meeting with Laba the guide dog and a white cane, because they are both blind. They have working at the ZAZ since it opened in 2019, despite their disability – in the office – thanks to a special voice computer programme.

– For us, as disabled people, work is very important – Waldemar emphasises. – It’s not only because we earn money to pay the bills; it gives us a lot of joy and a sense of self-esteem. It makes us feel that we are not a burden to society; we also pay taxes and save up for retirement.

– Work is social development, a type of rehabilitation – Alicja concurs. – There is nothing worse than sitting at home, while by doing this we feel needed, because we really want to do something.

– For people a little behind in development, like us, it is hard to find a job on the market – Grześ adds. – Often we have no education, and have not finished school, even vocational school. At the foundation, we found straightaway that the attitude was that we are to learn to work and try out various things, and see what works for us.

– Fundacja Różnosprawni and the ZAZ give me a sense of security. Before that, for fifteen years, I would go the job centre and find nothing, while here I am learning to be active professionally – Maciek says, – and how to behave with others in various situations. We are simply learning dignity here.

– Since the outset, our main goal has been to empower people with disabilities and for them to become self-reliant – Mateusz Smołucha, who is also the director of the ZAZ, explains. – The struggle to make them independent and give them a chance to fully contribute to community life is the subject with which we feel most at home. Soon after we set up the foundation, the ZAZ was opened, to help people with disabilities be active professionally. Organisations that help people with disabilities often have a tendency for pity. I take the opposite view, because I like to do things differently – I don’t think we should do things for other people, but instead create opportunities for action and provide support. For example, a few people who live in the homeless shelter work for us. Initially, that institution suggested that transportation would need to be provided, but we insisted that they come on their own using public transport, precisely in order to be self-reliant. And they come on their own (at first they practised with a coach), and moreover they are proud of that and like doing it, because it is always an opportunity to be among people and for social interaction.

Mateusz Smołucha knows what he is talking about, because in a way he is also talking about himself. He himself has a disability. He was worn a hearing aid for 25 years, and at times has experienced discrimination on that account. When I say that his disability cannot be seen, Agnieszka Rawska – the psychologist at the foundation – explains that there are many stereotypes and myths surrounding people with disabilities and mental illness. Those relating to appearance can be just as powerful as those relating to helplessness. The foundation is trying to break them down, – and build our employees’ self-confidence – foundation president Roksana Orzażewska says.

Meanwhile, Mateusz Smołucha stresses – none of our employees is completed disabled. Although people like to perceive similar people in that way – as people who need special treatment, to be careful around and pity. Their disability relates to some particular aspect – there are people with mental disability, autism, blind people, and people with mental illness. All the same, I don’t like the term person with disability – he adds and smiles – that makes it sound as if that disability is something I can leave at home, and tell myself, oh, I’m not taking it with me today. I prefer simply disabled.

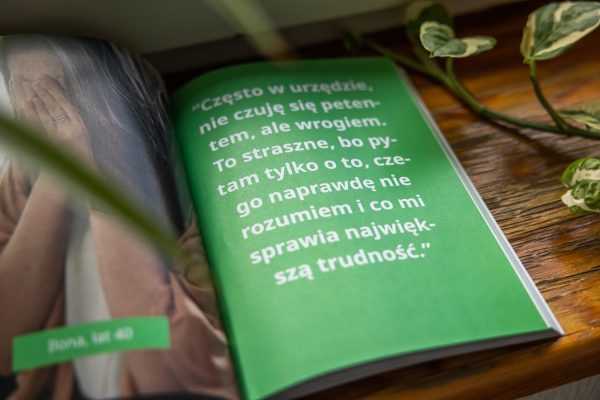

He adds that ZAZ employees have labour rights the same as any person employed in Poland. It was important to the foundation for them to learn what rights they have and to fight for them in other areas as well – being a patient, consumer, a person dealing with government authorities, or a member of a family. This is because long-term contact with people working at the ZAZ showed them many situations in life in which they do not know what to do. One example is being pestered with marketing text messages or dealing with some matter in a government office. They panic because they have not been taught how to behave. Parents often took the view that there was no point, and their entire lives they did things for their children.

Big thing

This is how the idea for the #prawoMOCNI project came about, for which the foundation was awarded a grant under the Active Citizens Fund – National Programme. The principal aim was to improve the participants’ ability to function in the community, and make them self-advocates.

– We wanted to show that these are people who are capable of working and functioning in society despite the view held by the public, one example of which is doing shopping or dealing with various other matters in government offices – Mateusz Smołucha says – they only need support, to be shown how to go about it, and build their self-confidence. It is not true that when a disabled person is given a task they have to be constantly supervised.

– One of our employees, who has autism, has just become an employment coach, which means they have begun leading their own renovation team; another dreams of starting a family, and another dreams of getting a driving licence and travelling to work abroad – says Elżbieta Bator, the vice-president.

– When they are on a break, our employees go on their own to do shopping in Biedronka, and then make themselves breakfast – Michalina Krowiak continues, who is responsible for PR and social media at the foundation. – with help from their family, Martyna and Mateusz rent a flat on our residential estate and take care of it themselves, have a dog, and go cycling together. For an able-bodied person, all of this is the normal routine; for them it is something big.

Participants in the project had classes on dealing with matters in government offices, daily decision-making, and budgeting (everyone has a bank account and knows how to make withdrawals from a cash machine), interests and hobbies, how to navigate the Internet safely, relationships and abuse in families, and dealing with practical and emotional matters when a loved one dies. There was also self-presentation and coaching on social skills.

– That was highly beneficial, because the project dealt with practically every aspect of our day-to-day lives – Waldek stresses. – We did rehearsals for those areas in practice – at a shop, government office, and library, supervised by coaches. When the project finished, I had no concerns when I went to the municipal council office, for example, where I knew that as a blind person they would help me fill in the right forms. Now I feel confident, and a have a sense of assurance that I will manage.

– The project made us realise that various institutions are there for us – Alicja emphasises. – We are entitled to expect them to deal with the matter concerned. I used to be scared to ask questions in a shop or government office, and today this is no longer a problem.

Maciek proudly takes out a laminated ticket for using public transport free of charge, which is an entitlement for people with disabilities. When the project had finished, he and Grzegorz obtained that ticket, and now the two of them travel not only to the ZAZ to work, but around the city, for example to go for a coffee.

– We learnt how to find information online and Maciek and I went on a trip to Wrocław – Grzegorz adds. – Due to earning money, I know that I can afford this and that.

– And recently, I warned an elderly neighbour about an attempt at data fraud – Adrian says. – If it wasn’t for the project, I would not have known that something was wrong.

They concluded the project with a social campaign to counteract disability stereotypes and promote self-advocacy – We did photo sessions, and made posters, videos and infographics, and advertised around the city – Michalina Krowiak says. – Our self-advocates had an opportunity to submit their recommendations and comments on the Kędzierzyn-Koźle City Development Strategy.

– When the city authorities recently invited our foundation to attend consultations on modifying spaces for the disabled, fourteen employees, not at management level, went to present their points of view, ask questions, and talk – Mateusz Smołucha stresses. – It is their viewpoint that counts. Officials were delighted with their active attitude.

A community centre for all

Utopia House – International Empathy Centre, Nowa Huta, Kraków, is a place created by the famous Nowa Huta Łaźnia Nowa Theatre. It is a venue for cultural and community events, with a community centre on the first floor for Roma children, created and run by Edyta Jaśkowiak and Sabina Antkowiak.

Edyta studied early years pedagogy, and is an artist at heart, as well as a born leader. Her Roma background has inclined her to be an activist since she was a teenager, because, she says, the Roma people are still one of the most discriminated against groups in Poland.

She began with activities on Roma residential estates with the artist Małgorzata Mirga-Tas, the same person who represented Poland in 2022 at the Biennale Venice with enormous vyshyvanka (embroidered blouses) pictures portraying life in Roma communities. In her professional life, Edyta is an education assistant. This involves assisting Roma schoolchildren in ten Kraków schools (in Kraków there are a mere three education assistants per 150 Roma children attending school). In addition to this, however, Edyta is involved in a range of other activities, and runs Roma dance workshops, which both Roma people themselves and Poles interested in that culture like to attend.

Sabina, Edyta’s cousin, also studied pedagogy, and has worked as a teacher at the community centre for ten years. Sabina and Edyta work together in aid of the Roma community.

The community centre they created was intended as a place where Roma children can come to do their homework and get help with Polish, mathematics, and other subjects, and they have art lessons.

– Polish presents them with a challenge at times – Edyta explains. – They are bilingual, and their first language is the Roma language, learnt at home, and therefore it is important to adopt the appropriate approach at school so that they get used to using Polish. As the official language, Polish can also present problems for adults, and thus over time pupils’ parents or grandparents began coming to the community centre as well, seeking help for example with drafting a document submitted to the authorities or advice on dealing with matters in various institutions. For two years, and since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, Ukrainian Roma people who fled to Poland have also been coming.

One example is Regina, who has popped in to the centre now. She came from Kirovohrad with five children aged between six and fourteen. Her husband, who used to work at a sawmill, is fighting in Ukraine and is part of a tank crew. In Poland, Regina’s teenage daughters had lessons at a Ukrainian school remotely, but were not willing to go to a Polish school.

– I convinced them to do that, using Edyta as an example – Sabina smiles. – They saw a young Roma woman, pretty, educated, and self-confident, knowledgeable about technology, and working, and on top of that holding dance classes that they really enjoyed. They wanted to be like her, and started going to school and coming to the community centre.

– Many of the Roma children, Ukrainian or Polish, are talented, but often they need to be encouraged, and given motivation to pursue an education – Edyta says. – I myself have the experience of wanting to stop studying a few times, for example not take the matriculation examination, but then Sabina motivated me and that helped me find the determination. If that had not happened I would not be where I am today.

– The stereotypes that Roma people do not finish school, that they steal, still exist and are very strong – Edyta Jaśkowiak continues – that is why I chose to study pedagogy. I wanted to change that, and I knew that education was sorely needed in our community.

She probably would have dealt mainly with education, had it not been for the war in Ukraine. When the war broke out, refugees of Roma origin started coming to Poland. It soon became clear that they were “excluded twofold”, and Polish volunteer networks and organisations are less willing to help Roma people fleeing the war than other refugee groups. Edyta, Sabina, and other Roma leaders from various places in Poland joined forces to find them flats, help them deal with administrative matters, or claim welfare benefits to which war refugees from Ukraine were entitled, such as 500+. An important aspect was convincing Roma children from Ukraine, like Regina’s daughters, to go to a Polish school. Sabina translated school reading material into the Roma language for them. That is a work in progress. Many children have gained an excellent command of Polish, but others are still unable to do that. There are constant problems with formalities, and refugees recommend their help to each over the grapevine.

Edyta stresses that it would be harder to become organised if they had not taken part in the “Liderki i liderzy romscy przeciwko wykluczeniu” (Roma leaders against exclusion) project conducted by the Central Council of Roma and the Roma Advisory and Information Center (carried out using grants under the Active Citizens Fund – National Programme).

We Roma, Polish citizens

The idea that the project’s architects had was to select ten or more people from throughout Poland, currently working in aid of the Roma community, like Edyta Jaśkowiak and Sabina Antkowiak. They wanted to provide them with the tools to be able to conduct the activities more efficiently, having the appropriate resources. This was all to counteract Roma people stereotypes and provide support for integration of this community.

– Roma Civil Monitor surveys show clearly that although Poland embarked upon measures, following EU accession, to ensure that the Roma community had equal opportunities, this group continues to struggle with strong stereotypes and exclusion – Karolina Kwiatkowska of the Central Council of Roma in Poland and project coordinator, says. – This applies to various areas. Equal opportunities in education, or for example access of the Roma people to the job market, are very important subjects. Employers are often reluctant to employ them due to stereotypes regarding dishonesty. The leaders – self-advocates – could do a lot in this regard.

– Poles often define Roma culture in terms of small villages in Małopolska, our music, or colourful knee-length skirts – Karolina Kwiatkowska adds. – while primarily it is the Romanipen Code that lays down the rules by which our community lives.

This code is unknown to the wider Polish public, and for this reason the role of self-advocates is particularly important. They become interpreters bridging the communication gap between cultures. To fulfil this role, they have to have an excellent knowledge of their own culture and have an understanding at the same time of the workings of the system in which broader society functions.

– In the project “Roma leaders against exclusion”, they received an infusion of knowledge about the law, and we also taught them how to work effectively with various institutions – local government, voivodship authorities, welfare centres, and institutions in the education system – Karolina Kwiatkowska explains. – So that they could teach those institutions to understand our culture and how to work with the Roma people on the one hand, and advise the Roma people themselves on the rules they have to observe on the other. For example, to submit a document in writing when dealing with some formality, as Roma culture puts great store by the spoken word, which by itself is a form of contract, while this is not enough in a Polish government office. This may seem trivial, but it is very important.

Communicating effectively was another very important topic. The architects of the project were very keen for the leaders taking part to be able to demonstrate that the Roma people play a part in creating community and civic life.

– We want to be a part of it, because the Roma people are also Polish citizens – Karolina Kwiatkowska stresses – we want to become integrated in Polish society but also retain our cultural identity without that meaning that we are seen in terms of stereotypes. Above all, we need to get to know each other, as we will not move forward otherwise.

Since the project ended, Edyta Jaśkowiak has created a campaign to raise awareness about the Roma people, and attended talks with the city authorities. In 2022, she was awarded the title of Kraków Ambassador of Multiculturalism.

– In my work, I had been a self-advocate for a long time, talking about the needs of the Roma people, encouraging them to talk about that themselves, and seeking ways of solving various difficult issues – Edyta says. – Meanwhile, the project “Roma leaders against exclusion” helped me to develop my self-advocating skills a lot. I learnt that it is worthwhile talking about oneself and one’s achievements. In the past, I was not very inclined to talk about my successes, but this made me realise that I can’t stand quietly on the sidelines. It is important not only for me, but for the Roma people as well, for them to be aware that it is worth getting an education, developing, and achieving their dreams. This changes the way our entire group is perceived. When I was given the award, I felt that I was acting on behalf of all Roma activists. This confirms that it is possible to reconcile our identity with functioning properly in society.

The Ktoś Foundation project “O nas z nami” (About us with us), Fundacja Różnosprawni project #prawoMOCNI Fundacji, and Central Council of Roma and the Roma Advisory and Information Center project “Roma leaders against exclusion” were conducted using funds from the Active Citizens Fund – National Programme funded by Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway using EEA Funds.

Text: Agnieszka Wójcińska

Photo: Anna Liminowicz

The report was published on Onet.pl